Scientists have unveiled a detailed snapshot of human migrations in Europe during the first millennium AD by employing a more precise method of analysing ancestry through ancient DNA.

Documenting migrations by analysing changes in DNA has proven difficult due to the presence of historical groups of genetically similar people.

For the latest study, however, researchers employed a new method of analysis to over 1,500 European genomes from the first millennium AD, spanning the Iron Age, the fall of the Roman Empire, the early medieval “Migration Period” and the Viking Age.

The new method of measuring DNA changes allowed researchers from the Francis Crick Institute in the US to differentiate even genetically very similar groups.

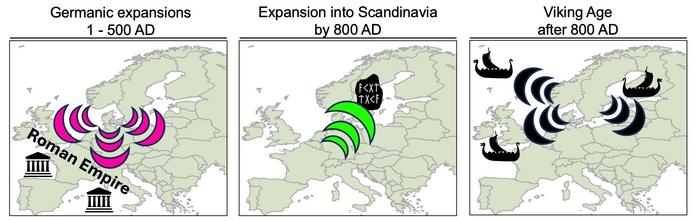

The study, published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, revealed previously unknown migrations. It showed waves of Romans migrating south from northern Germany or Scandinavia early in the first millennium, providing genetic evidence to back existing historical records of this movement.

The research identified Roman ancestry in individuals from southern Germany, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, and southern Britain, with one person in southern Europe exhibiting 100 per cent Scandinavian-like ancestry.

Many of these groups eventually mixed with older populations, the researchers said.

The study found that most of the migrations involved people speaking three main branches of Germanic languages.

One of these populations remained in Scandinavia, another spoke a language that later became extinct, and the third formed the basis of modern German and English.

The study also identified descendants of Roman gladiators within the ancient population.

It found that a quarter of the ancestry of an individual who lived in York, Britain, between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD would have come from a Roman soldier or slave gladiator from early Iron Age Scandinavia.

This indicates that people with Scandinavian ancestry were present in Britain earlier than the Anglo-Saxon and Viking periods, which began in the 5th century AD.

The study also found evidence of a northward wave of migration into Scandinavia at the end of the Iron Age, between 300 and 800AD, just before the Viking Age. Many Viking Age people across southern Scandinavia carried ancestry from central Europe.

The findings suggest that repeated conflicts and unrest in Scandinavia during this period played a role in driving the migrations.

However, more archaeological, genetic, and environmental data are needed to confirm this, the researchers said.

Scholars generally believed that during the Viking Age, people from Scandinavia raided and settled across Europe.

The new study revealed that many people outside Scandinavia during this period had a mix of local and Scandinavian ancestry, supporting historical records. For instance, some Viking Age individuals in what is now Ukraine and Russia had ancestry from present-day Sweden, while those in Britain from this time had ancestry from present-day Denmark.

Mass graves in Britain dated to this period contain the remains of men who died violently and show genetic links to Scandinavia.

This suggests they may have been executed members of Viking raiding parties.

The research provides fresh insights into migrations across Europe during the first millennium, originating in northern Europe during the Iron Age and then returning to Scandinavia before the Viking Age.

“Robust analyses of finer-scale population changes, like the migrations we reveal in this paper, have largely been obscured until now,” the study’s first author, Leo Speidel, said.

“Our new method can be applied to other populations across the world and hopefully reveal more missing pieces of the puzzle.”

Source: independent.co.uk